Previous Section

Part 1: Observations of Global Properties

Part 2: Homogeneity and Isotropy; Many Distances; Scale Factor

Part 3: Spatial Curvature; Flatness-Oldness; Horizon

Part 4: Inflation; Anisotropy and Inhomogeneity

FAQ |

Tutorial :

Part 1 |

Part 2 |

Part 3 |

Part 4 |

Age |

Distances |

Bibliography |

Relativity

Inflation

The "inflationary scenario", developed by Starobinsky and by Guth,

offers a solution to the flatness-oldness problem and the

horizon problem. The

inflationary scenario invokes a

vacuum

energy density. We normally think of the vacuum as empty and

massless, and we can determine that the density of the vacuum is

less than 1E-30 gm/cc now. But in quantum field theory, the vacuum

is not empty, but rather filled with virtual particles:

The space-time diagram above shows virtual particle-antiparticle

pairs forming out of nothing and then annihilating back into

nothing. For particles of mass m, one expects about one

virtual particle in each cubical volume with sides given by

the Compton wavelength of the particle, h/mc, where h is

Planck's constant. Thus the expected density of the vacuum

is rho = m4*c3/h3

which is rather large. For the largest

elementary particle mass usually considered, the Planck mass M defined

by 2*pi*G*M2 = h*c, this density is 2E91 gm/cc. Thus the vacuum

energy density is at least 121 orders of magnitude smaller than

the naive quantum estimate, so there must be a very effective

suppression mechanism at work. If a small residual vacuum

energy density exists now, it leads to a

"cosmological constant"

which is one proposed mechanism to relieve the tight squeeze

between the Omegao=1 model

age of the Universe, to = (2/3)/Ho =

10 Gyr, and the apparent age of the oldest globular clusters,

16+/-4 Gyr. The vacuum energy density can do this because

it produces a "repulsive gravity" that causes the expansion of

the Universe to accelerate instead of decelerate, and this

increases to for a given Ho.

The inflationary scenario proposes that the vacuum energy was

very large during a brief period early in the history of the

Universe. When the Universe is dominated by a vacuum energy

density the scale factor grows exponentially,

a(t) = exp(H(to-t)). The Hubble constant really is constant

during this epoch so it doesn't need the "naught".

If the inflationary epoch lasts long enough the exponential

function gets very large. This makes a(t) very large,

and thus makes the radius of curvature of the Universe

very large. The diagram below shows our

horizon superimposed

on a very large radius sphere on top, or a smaller sphere on

the bottom. Since we can only see as far as our horizon,

for the inflationary case on top the large radius sphere

looks almost flat to us.

This solves the flatness-oldness problem as long as the exponential

growth during the inflationary epoch continues for at least 100

doublings.

Inflation also solves the horizon problem, because the future lightcone

of an event that happens before inflation is expanded to a huge

region by the growth during inflation.

This space-time diagram shows the inflationary epoch tinted green,

and the future lightcones of two events in red. The early event

has a future lightcone that covers a huge area, that can easily

encompass all of our horizon. Thus we can explain why the temperature

of the microwave background is so uniform across the sky.

Details: Large-Scale Structure and Anisotropy

Of course the Universe is not really homogeneous, since it contains

dense regions like galaxies and people. These dense regions should

affect the temperature of the microwave background.

Sachs and Wolfe (1967, ApJ, 147, 73) derived the effect of the

gravitational potential perturbations on the CMB. The

gravitational potential,

phi = -GM/r, will be negative in dense lumps, and positive in

less dense regions. Photons lose energy when they climb out of

the gravitational potential wells of the lumps:

This conformal space-time diagram above shows lumps as gray vertical

bars, the epoch before recombination as the hatched region, and

the gravitational potential as the color-coded curve phi(x). Where

our past lightcone intersects the surface of recombination, we see

a temperature perturbed by dT/T = phi/(3*c2).

Sachs and Wolfe predicted temperature fluctuations dT/T as large

as 1 percent, but we know now that the Universe is far more

homogeneous than Sachs and Wolfe thought. So observers worked

for years to get enough sensitivity to see the temperature

differences around the sky. The first anisotropy to be detected was the

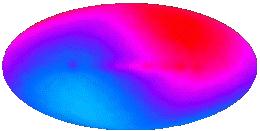

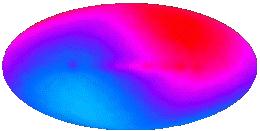

dipole anisotropy by Conklin in 1969:

The map above is from

COBE

and is much better than Conklin's 2 standard deviation detection.

The red part of the sky is hotter by (v/c)*To, while the blue

part of the sky is colder by (v/c)*To,

where the inferred velocity is

v = 370 km/sec. This is how we measure the velocity of the Solar System

relative to the observable Universe.

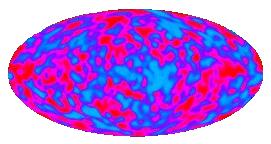

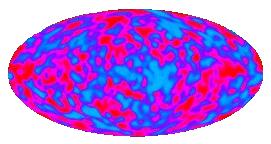

It was another 23 years before the anisotropy predicted by Sachs and Wolfe

was detected by Smoot \etal in 1992. The amplitude was 1 part in

100,000 instead of 1 part in 100:

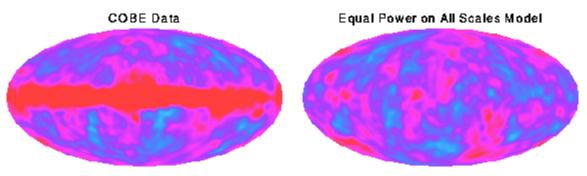

The map above shows cosmic anisotropy (and detector noise) after

the dipole pattern and the radiation from the Milky Way have been

subtracted out.

The anisotropy in this map has an RMS value of 30 microK, and if it is

converted into a gravitational potential using Sachs and Wolfe's result

and that potential is then expressed as a height assuming a constant

acceleration of gravity equal to the gravity on the Earth, we get a

height of twice the distance from the Earth to the Sun. The "mountains

and valleys" of the Universe are really quite large.

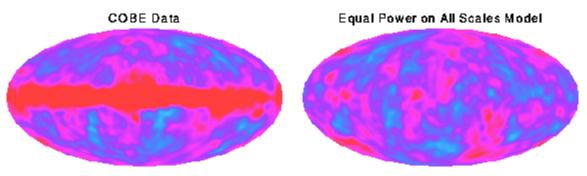

Inflation predicts a certain statistical pattern in the anisotropy.

The quantum fluctuations normally effect very small regions of space,

but the huge exponential expansion during the inflationary epoch

makes these tiny regions observable.

The space-time diagram on the left above shows the future lightcones

of quantum fluctuation events. The top of this diagram is really a

volume which intersects our past lightcone making the sky. The

future lightcones of events become circles on the sky. Events

early in the inflationary epoch make large circles on the sky, as

shown in the bottom map on the right. Later events make smaller circles

as shown in the middle map, but there are more of them so the sky coverage

is the same as before. Even later events make many small circles which

again give the same sky coverage as seen on the top map.

The pattern formed by adding

all of the effects from events of all ages is known as

"equal power on all scales", and it agrees with the COBE data.

Having found that the observed pattern of anisotropy is consistent

with inflation, we can also ask whether the amplitude implies

gravitational forces large enough to produce the observed clustering

of galaxies.

The conformal space-time diagram above shows the phi(x) at recombination

determined by COBE's dT data, and the worldlines of galaxies which are

perturbed by the gravitational forces produced by the gradient of the

potential. Matter flows "downhill" away from peaks of the potential

(red spots on the COBE map), producing voids in the current distribution

of galaxies, while valleys in the potential (blue spots) are where the

clusters

of galaxies form.

COBE

was not able to see spots as small as clusters or even superclusters

of galaxies, but if we use "equal power on all scales" to extrapolate

the COBE data to smaller scales, we find that the gravitational forces

are large enough to produce the observed clustering, but only if these

forces are not opposed by other forces. If the all the matter

in the Universe is made out of the ordinary chemical elements, then

there was a very effective opposing force before recombination,

because the free electrons which are now bound into atoms were very

effective at scattering the photons of the cosmic background.

We can therefore conclude that most of the matter in the Universe

is

"dark matter" that does not emit, absorb or scatter light.

This strange conclusion will be greatly strengthened by temperature

anisotropy data at smaller angular scales which will be

provided by the

Microwave Anisotropy Probe (MAP)

in the year 2000.

Ned Wright's home page

FAQ |

Tutorial :

Part 1 |

Part 2 |

Part 3 |

Part 4 |

Age |

Distances |

Bibliography |

Relativity

© 1996-1998 Edward

L. Wright. Last modified 7-Dec-1998